Create Bash script with options, commands and arguments

Bash-script with options.

To streamline their workflow as a programmer, in a server or Linux environment, it is good to know the commands that are available. When you want to make multiple commands in a row, you gather them into a script.

To go one step further, you can build the script as a program that can take options, commands and arguments to these commands.

In this article we look at how we build a script so it looks like a regular program that can take options, commands and arguments.

#A command line program in Bash

#Download

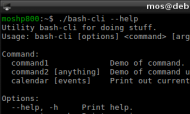

In the GitHub-repository for the unix-course there is an example program called bash-cli. The program shows a basic structure that can be used to create command line programs with Bash.

If you have already cloned a course repo, you will find the sample program in the following directory.

$ cd unix/example/bash/cli-with-options/

#Test the script

Let’s see how the script works and what its code looks like. We start with a visual example when we run the command.

#Usage

In the video above, I ran the program as follows.

| option, command, argument | Description |

|---|---|

| nothing | The program shows a text on how to get help using it. |

--help or -h |

Show a help text about how the program can be used and its various options. |

--version or -v |

View the program version. |

command1 |

Simulates a command by displaying a simple print. |

command2 and command2 with argument |

Simulates a command that can take any number of arguments. |

calendar and calendar events |

A command that displays a calendar along with events that happened on today’s date. |

That’s all the program managed, let’s see what the code behind it looks like.

#A template for a command line application

We take a look at the code in bash-cli, top to bottom.

The first lines are a [shebang] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shebang_(Unix)) followed by some comments that tell you what the script is about.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

#

# A template for creating command line scripts taking options, commands

# and arguments.

#

# Exit values:

# 0 on success

# 1 on failure

#

Then follows a couple of global variables about the script itself. I choose to name these variables in capital letters to distinguish between global and local variables.

# Name of the script

SCRIPT=$( basename "$0" )

# Current version

VERSION="1.0.0"

First, it is the name of the script and then its version.

Following are a few features used to print help text and version information.

First, the function that prints the help text.

#

# Message to display for usage and help.

#

function usage

{

local txt=(

"Utility $SCRIPT for doing stuff."

"Usage: $SCRIPT [options] <command> [arguments]"

""

"Command:"

" command1 Demo of command."

" command2 [anything] Demo of command using arguments."

" calendar [events] Print out current calendar with(out) events."

""

"Options:"

" --help, -h Print help."

" --version, -v Print version."

)

printf "%s\n" "${txt[@]}"

}

It is a local variable that is an array of strings, so you can write the text so that it is easy to format.

There is a similar function badUsage which is used if the user uses the script incorrectly.

#

# Message to display when bad usage.

#

function badUsage

{

local message="$1"

local txt=(

"For an overview of the command, execute:"

"$SCRIPT --help"

)

[[ $message ]] && printf "$message\n"

printf "%s\n" "${txt[@]}"

}

The function badUsage may or may not make an argument. If an argument is passed to the function, it is printed as a message.

Here’s how to call a function in Bash, with or without arguments.

badUsage "Option/command not recognized."

badUsage

Then there is the function for printing the version of the program.

#

# Message to display for version.

#

function version

{

local txt=(

"$SCRIPT version $VERSION"

)

printf "%s\n" "${txt[@]}"

}

Here, there may seem to be a bit of a ambitious with an array for the text that is only one row long. The purpose was to do this function in the same way as the other functions.

The function’s body could have been written simpler, much like this.

# With printf

printf "%s version %s\n" "$SCRIPT" "$VERSION"

# or with echo

echo "$SCRIPT version $VERSION"

As we continue, we jump to the last part of the program.

#Check all arguments

The last part of the code is a while loop and a case statement that goes through all the arguments that are sent to the program. Here I just call it arguments, at this level everything that is sent to the program arguments.

First, let’s simplify the code.

#

# Process options

#

while (( $# ))

do

case "$1" in

--help | -h)

usage

exit 0

;;

--version | -v)

version

exit 0

;;

# more code...

esac

done

The built-in variable $# tells the number of arguments and in each loop the first argument $1 is tested in the list of arguments.

The case statement checks if the argument is known. In the first part we check if the argument to my script is an * option * that matches --help, -h, --version or -v.

So that’s how my script takes in the arguments. Then the arguments are interpreted and the script decides whether they are options, commands or arguments. Those who start with a minus sign, I call options. (You can read briefly about why there are two types of options, with one or two minus characters.)

If there is a hit, a function is called that either prints the version number or the help text, then the program is canceled with a positive exit code which is 0.

If you pass an argument that is not recognized, an error message is printed using the function badUsage and the exit code becomes 1 which in Bash context is considered an error code.

#

# Process options

#

while (( $# ))

do

case "$1" in

# more code...

*)

badUsage "Option/command not recognized."

exit 1

;;

esac

done

badUsage

exit 1

Now let’s look at what I call commands and the ability to send arguments to a command. We return to the case statement.

#

# Process options

#

while (( $# ))

do

case "$1" in

# more code...

command1 \

| command2 \

| calendar)

command=$1

shift

app-$command $*

exit 0

;;

# more code...

esac

done

Here I choose a variant to interpret all possible commands in a part of the case statement. If it is a hit, for example on the calendar command, then the functionapp-calendar is called and any remaining arguments $ * are pass to that function.

I have chosen this way to name the function, with a prefix of app, to make my own code clear and organize it.

So for each command, I write a function that is called and handles each command. This is what the app-calendar function looks like.

#

# Function for taking care of specific command. Name the function as the

# command is named.

#

function app-calendar

{

local events="$1"

echo "This is output from command3, showing the current calender."

cal

if [ "$events" = "events" ]; then

echo

calendar

fi

}

The function prints the calendar via the external command cal and a list of events via the external command calendar, provided that the argument "calendar events" is submitted.

#Support for more commands

As the script gets bigger and bigger, it becomes easy to fill in with new commands. What is needed is a function app-commandx and a row in the case statement corresponding to commandx.

Then you should not forget to update the function usage as well, so the command is documented. It is always easy to forget what you did, so document what you did and how you thought it would be used.

#Finally

Overall, the script bash-cli becomes a template and structure for command-line programs that can take options, commands and arguments into a command.

Sometimes it may not be obvious what should be just options, commands and arguments. But let logic rule and try different things. You will learn how other programs are designed and you will see a structure that is commonly used among similar programs. It is good to follow a similar structure, as the user recognizes him- or herself.

#Revision history

- 2019-08-20: (A, lew) First edition.